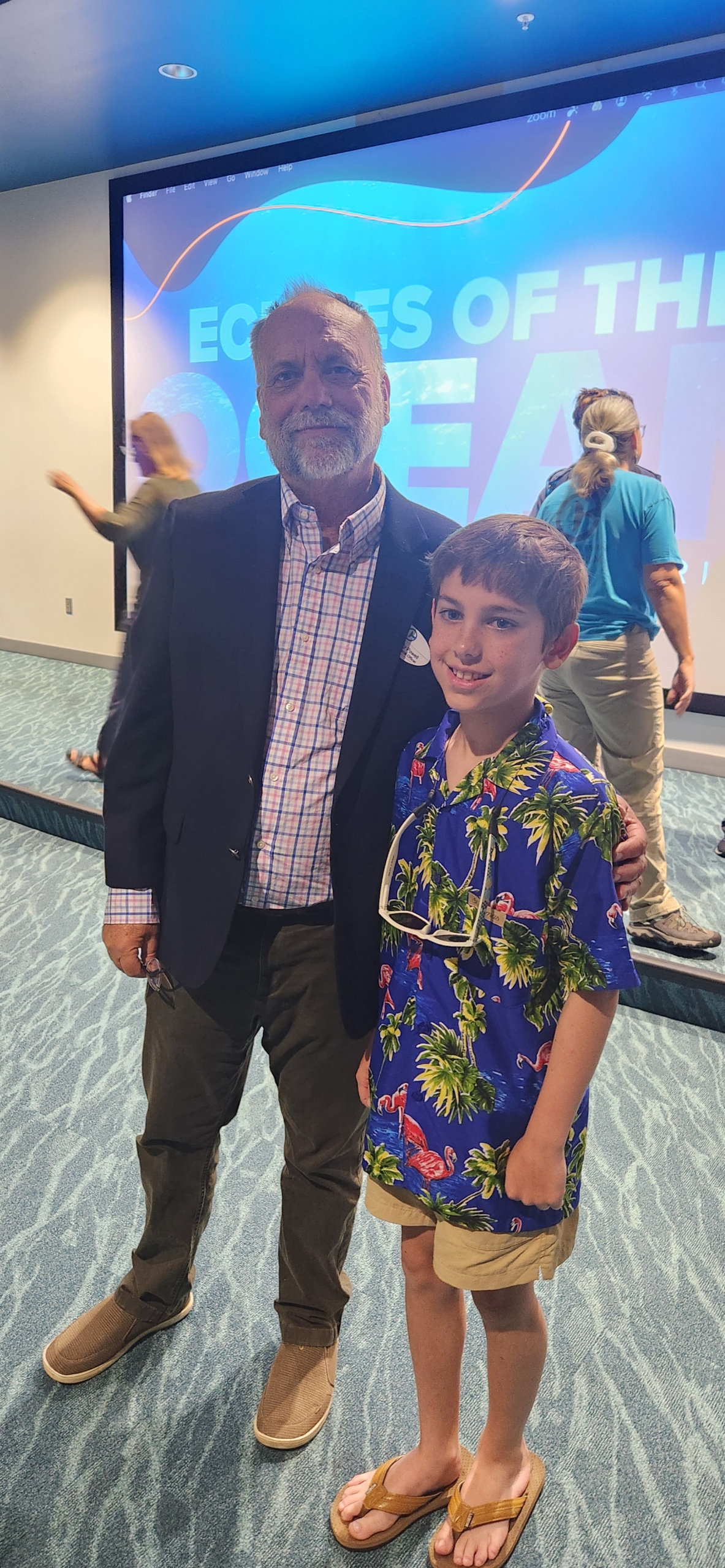

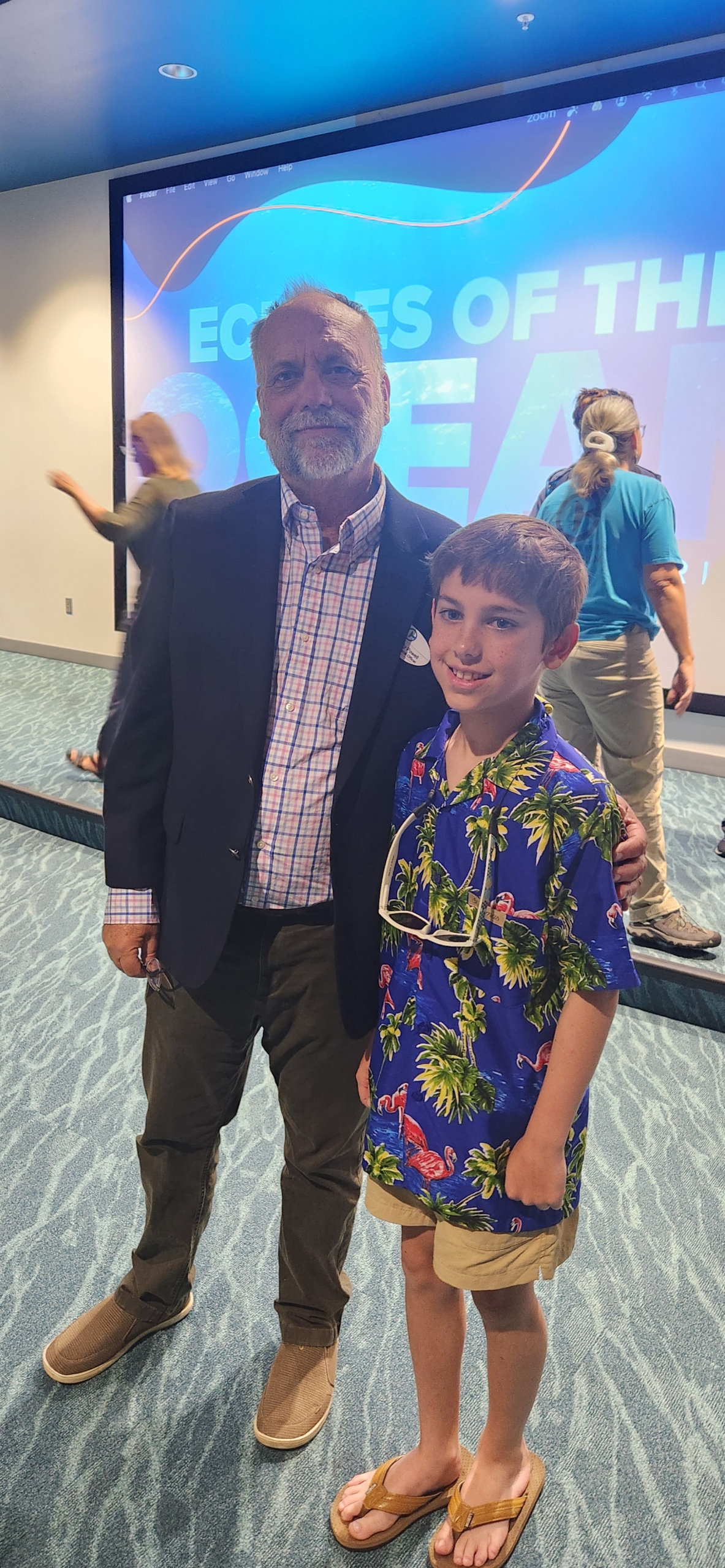

In 2005, when James “Buddy” Powell was Director of Aquatic Conservation for Wildlife Trust, SDRP colleague Nadine Slimak had the opportunity to interview him for a feature story. We think the anecdotes and highlights Buddy shared captured his spirit as a conservation biologist and a friend. With news of his passing in July 2025, we thought we would share his story with you. — SDRP

Long before Florida became one of the nation’s most visited states, before snorkelers and divers descended en masse on the tiny town of Crystal River to swim with the manatees, Dr. James A. “Buddy” Powell decided to give it a shot.

Powell, first introduced to manatees while fishing with his dad on the river when he was 5 or 6 years old, was always curious about the lolling mammals – and rather wary of them. “No one really knew anything about them back then, but I was always sort of curious,” says Powell, who at 51, now recounts the story of himself as a teenaged kid sitting on the edge of a boat, screwing up his courage to get in the water near a manatee. For a man whose life work has since been focused on manatees and their cousins the dugongs, you’d think the experience would have been some sort of epiphany.

Wrong.

“It was a frightening experience for both of us,” he says. One look at Powell, and the manatee spurted away in a splash and great spray of water. “I was terrified. I jumped in the water and then jumped right back out.” While it might not have been the most auspicious start to a career as a conservation biologist for a man who now heads up the Edge of the Sea Aquatic Conservation Program for the Wildlife Trust, it did nothing but distill Powell’s curiosity.

In 1967, when Powell was about 14, he finally met someone who could help answer some of his questions about the animals that he was growing up around. “One day I saw this guy with long hair and a ponytail standing up in the middle of a Sears johnboat and not fishing. I thought ‘He’s not from around these parts.’ He would stand there and look across the water using these binoculars. After a while, my curiosity got the best of me.”

After watching this hippie — it was 1967, after all — day after day, Powell finally introduced himself to Daniel S. Hartman, then a graduate student at Cornell University, who was studying manatees for his dissertation. Hartman became the first biologist to study manatees in depth, and he took Powell along for the ride. “I had this curiosity about wildlife, and I could ask questions, and he could answer them,” Powell says. “I became his sidekick/assistant. He was like a big brother to me.”

On summer days and in the mornings before school and afternoons when school let out, Powell and Hartman plied the waters around Crystal River, performing the first studies of a then little-known species. Powell taught Hartman the local knowledge needed for navigating area waterways, and Hartman taught Powell about biology. The work led Hartman to write about manatees for National Geographic magazine where some of Powell’s manatee photographs were published, and, eventually, a Jacques Cousteau documentary in which Cousteau recognized “the young Buddy Powell” for his help putting together the program.

Those studies became the basis for future investigations into manatee behaviors and the threats their populations now face worldwide; the work is still often cited by today’s scientists who are doing their own studies. They also led Powell to conservation biology. He left high school a year early for Stetson University and, eventually, his career led to manatee studies in Florida and in far-flung places such as West Africa and Belize for both governmental and non-governmental organizations. Along the way, he learned the importance of working with local residents and governments to help them protect their own resources. He also had the opportunity to begin teaching new generations of scientists.

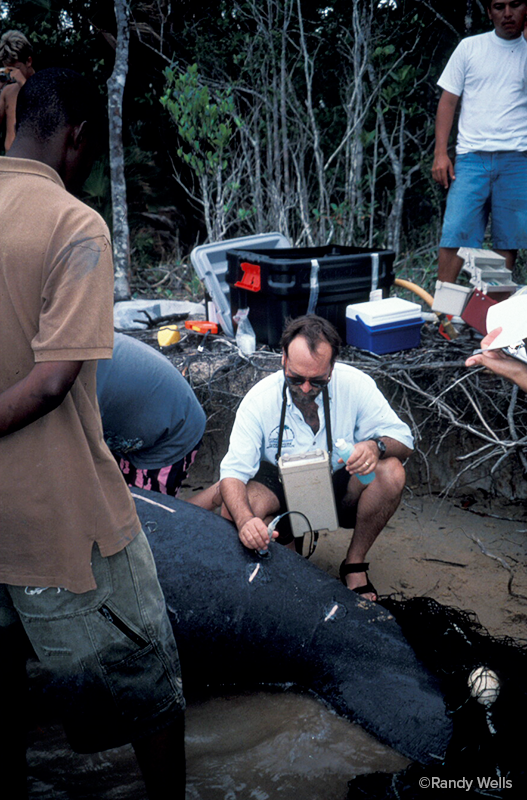

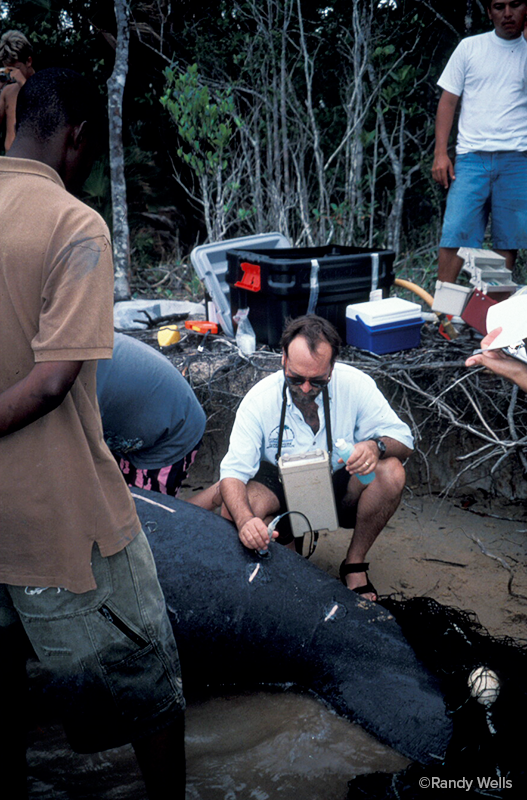

Working with locals and teaching those he worked with started early in his career, during his first attempts at tagging manatees in West Africa. “It took me eight months to find, catch and tag a manatee,” Powell says. “And it ended up in a fisherman’s stew pot.”

With an assistant, he was doing aerial surveys and interviewing local fisherman to find the best locations to tag manatees and track their movements for the Azagny National Park in Ivory Coast so the government could create a manatee management plan. After eight months of work, he finally captured, tagged and released a manatee. The animal was tagged with a radio transmitter that allowed Powell to follow its movements.

“This manatee would make a two-week circuit between the place where I tagged it and a small lagoon,” he said. “I had been tracking it for a couple of months. It was steaming back from the lagoon, following its usual pattern, and I was picking up the signal from my camp. The next morning, I couldn’t hear the signal.”

Powell left camp to attend to business in the city. As he returned the next day, he tried again to track the animal. Sure enough, he picked up a signal. Unfortunately it was coming from the village.

“My assistant and I go traipsing through this village (tracking the signal), and we finally find a fisherman mending his nets,” Powell says. By that time, the signal was blasting from where they were standing. Powell asked about the manatee — the fisherman said he hadn’t seen a manatee — but Powell found a piece of the belt that the transmitter had been attached to and, after digging into the dirt with his machete, found the actual transmitter itself. “I’m furious and everyone’s kind of gaping at us.”

Powell stormed off to get the forest guard — the preserve’s version of a game warden — and returned the next morning. The hunter was jailed. “While he was there, I started talking to him. He knew a lot about manatees, and I thought that his information would dramatically help improve our chances at capturing them to tag.”

And it did. “The first night, we caught one, the second night we caught two. And that was all of my tagging equipment.”

As for the charge of illegally hunting Powell’s first manatee, the hunter was eventually fined by the chief of the tribes who decided by local custom — that is, the person who first speared the manatee was the only one who could kill it — that the manatee was Powell’s. “He got fined a case of beer and a goat,” Powell said. “They had government law, but the cultural law — the more traditional law — was so much more powerful.”

After that, none of Powell’s tagged manatees ever ended up in a stewpot. He also was able to win over the support of the local residents.

Powell’s assistant in that work, and later the manatee hunter’s son, eventually went on to their own doctoral studies in biology and conservation. “That study really set the stage for a whole lot of things,” Powell says. “It taught me that the locals are essential in helping protect a resource, if they understand why it’s important.”

And when Powell received a prestigious Pew Fellowship Award in Marine Conservation in 2000, he was able to build programs to help train the next generation of conservation biologists. He continued enlisting new young scientists while creating and overseeing the Edge of the Sea Program since joining the Wildlife Trust in 2001. The Trust’s Edge of the Sea work includes a project monitoring the right whale population in the Atlantic Ocean from South Carolina to Florida. Right whales are among the most endangered species in the ocean, with an estimated 300 animals facing increasing threats from boat strikes by commercial vessels and entanglement in fishing gear.

“The right whale is one species that we’re working on now that if we don’t do something about the problems now — about reducing the threats these animals face — they won’t be around for my daughter,” Powell says. “As a conservation biologist, I’m always asking ‘Why are we here, and what are we doing?’ But there’s also this emotional component. One of the main reasons I do what I do is for the love of the animals and being able to experience them. If right whales go extinct, it won’t be on my watch.”