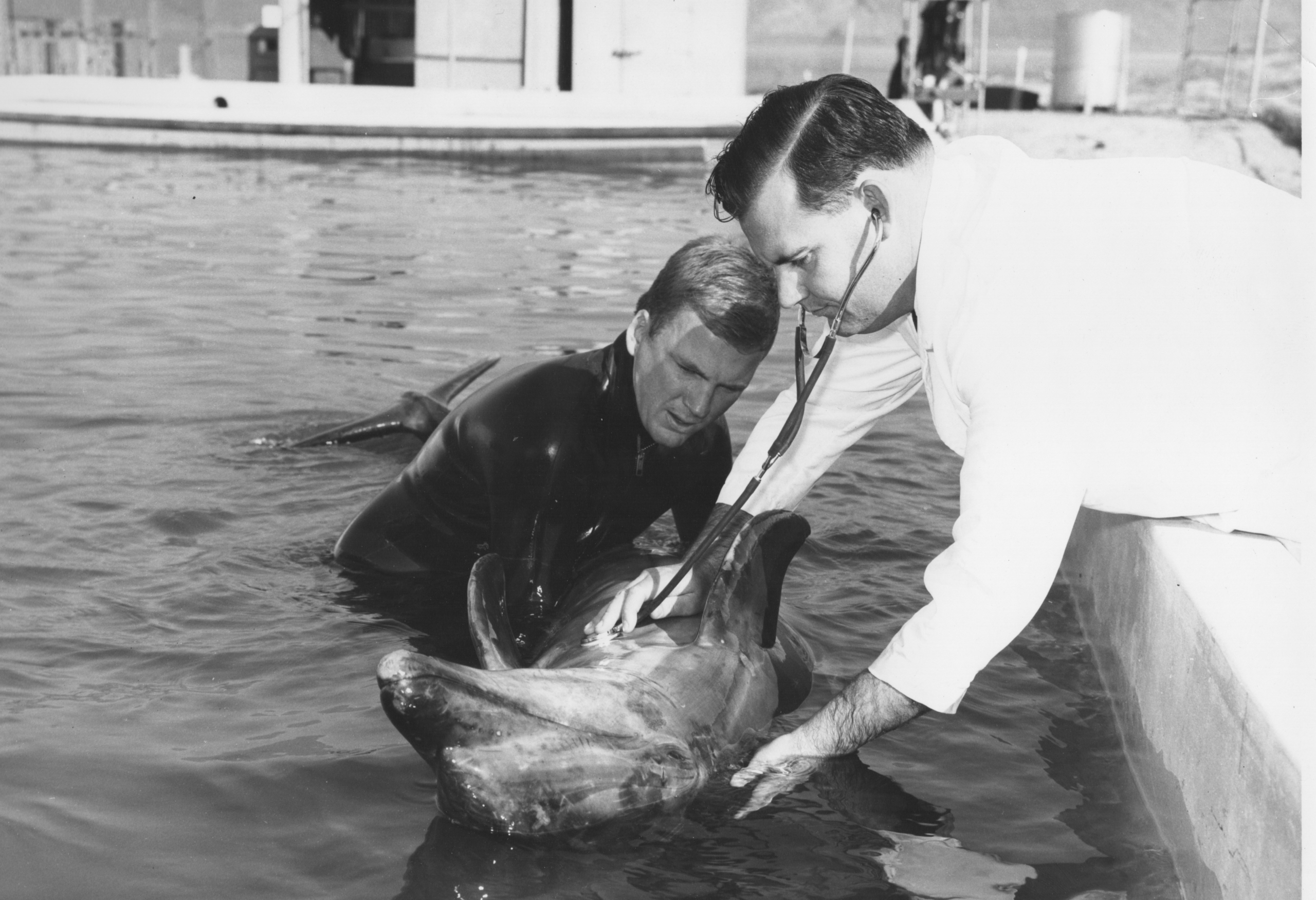

SDRP Founder Blair Irvine (left) and Sam Ridgway, 1967.

The marine mammal scientific community has lost two of the field’s greats: Sam Ridgway and William F. Perrin. These founders of modern marine mammal science were indirectly involved in the creation and development of the Sarasota Dolphin Research Program (SDRP), and their contributions to cetacean conservation cannot be overstated.

Sam Houston Ridgway, DVM, Ph.D., was 86 when he passed away on July 10 surrounded by family and friends. He is considered the father of marine mammal medicine, contributing much to what we know today about the physiology and veterinary care of marine mammals. Sam helped to found the U.S. Navy’s Marine Mammal Program, and helped to guide it for more than 50 years. In 2007, he established the National Marine Mammal Foundation (NMMF) — becoming its founding president and CEO. The nonprofit NMMF is dedicated to answering critical questions about the health of the world’s marine mammals and our shared oceans and has been extensively engaged in conservation medicine activities around the world.

SDRP founder Blair Irvine worked for Sam as part of the U.S. Navy program during 1965-1969, before moving to Sarasota, Florida, where he founded the SDRP in 1970. Sam was a model of easygoing but decisive leadership, says Irvine. “He was a wonderful friend and colleague who contributed to science while creating goodwill throughout his life.”

Over the years, we have been involved in a number of collaborations with the amazing staff of the NMMF, including development of health indices, examining the impacts of environmental contaminants, including the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, and studying the effects of multiple stressors on dolphins.

In 2017, I worked with Sam and the NMMF on an international collaboration to try to save the remaining vaquita porpoises from illegal fishing nets. His insights from decades of experience and his novel ideas contributed greatly to shaping our approach to this difficult problem.

Bill Perrin, Ph.D. and Senior Scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) Southwest Fisheries Science Center, was 83 when he passed away on July 11 in La Jolla, California. Bill’s accomplishments spanned nearly 50 years and included pioneering studies on dolphin taxonomy, life history, population ecology, conservation and behavior. He set high standards for those of us who followed.

His early work brought attention to the growing issue of large-scale dolphin deaths in the tuna purse seine fishery in the eastern Tropical Pacific — one of the issues that led to the creation of the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, which still protects dolphins and whales in U.S. waters today. SDRP co-founder Michael Scott has worked with Bill on this issue since the 1980s. “One of the first NMFS scientists I met was Bill Perrin,” Scott said. “It was hard not to be awed by his gruff-looking exterior and penetrating gaze, but eventually I learned that his gaze was often full of mischief, and that inside that gruff exterior was a warm-hearted and modest man. He was the most efficient scientist I know, accomplishing in one day what normally took me about three.”

Bill facilitated getting our research team from the University of California, Santa Cruz, led by Ken Norris, to Hawaii during 1979-1981 to study spinner dolphin behavior as part of the NOAA research efforts to better understand the dolphin species involved in the tuna fishery. One of my doctoral dissertation chapters was focused on spinner dolphin reproductive behavior. I, too, experienced the “gruff exterior and penetrating gaze” as Bill served on my dissertation committee. He was by far the toughest member of my committee, but his scientific rigor led to a much-improved product. He maintained incredibly high standards for quality in his own work, expected the same from others, and our field benefited greatly as a result.

Both men were recipients of the Society for Marine Mammalogy’s Kenneth S. Norris Lifetime Achievement Award, which recognizes recipients for careers that have significantly altered the course of marine mammal science. Both Bill and Sam greatly influenced the field through their research, through their mentoring of subsequent generations of scientists and veterinarians and through their leadership on the issues faced by marine mammals.

They will be greatly missed.

Randy Wells

Vice President of Marine Mammal Conservation

Director, Chicago Zoological Society’s Sarasota Dolphin Research Program