Studying the Impacts of Plastics and Plastic Compounds in Sarasota Bay Dolphins

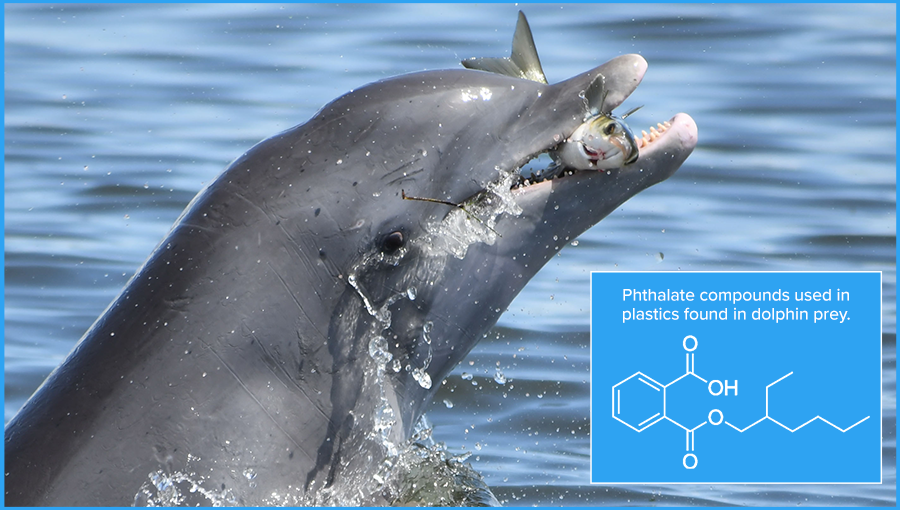

The oceans are estimated to contain more than 170 trillion plastic particles — with more than 90%  classified as microplastics less than 5mm (about the size of a pencil eraser). While impacts from marine life ingesting these particles are increasingly documented, a new area we’re investigating is the prevalence of exposure to the chemicals added to plastic to enhance their durability and flexibility. These chemicals are phthalate acid esters, also called phthalates or plasticizers. In fact, chemical additives can comprise more than 50% of some plastics, and the commercial market for chemical plasticizers is anticipated to grow.

classified as microplastics less than 5mm (about the size of a pencil eraser). While impacts from marine life ingesting these particles are increasingly documented, a new area we’re investigating is the prevalence of exposure to the chemicals added to plastic to enhance their durability and flexibility. These chemicals are phthalate acid esters, also called phthalates or plasticizers. In fact, chemical additives can comprise more than 50% of some plastics, and the commercial market for chemical plasticizers is anticipated to grow.

In recent years, using urine samples collected during routine Sarasota Bay dolphin health assessments, our team has detected prevalent phthalate exposure among dolphins here — phthalates have been found in about 75% of samples tested. Unlike other environmental contaminants studied in Sarasota dolphins (for example, PCBs), phthalate exposure does not appear to be tied to age or sex, suggesting widespread susceptibility.

While demographic characteristics might not influence phthalate exposure in dolphins, where the dolphins spend their time might.

Exposed dolphins tended to be those who spent their time within closed embayments in the southern portion of Sarasota Bay, while unexposed dolphins were found in more open waters to the north. The most commonly detected metabolites in Sarasota Bay bottlenose dolphin urine are monoethyl phthalate (MEP) and mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP), which are metabolites of parent compounds commonly added to personal care products and plastic.

Phthalate exposure is also monitored in studies conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and comparisons to these human reference populations revealed significantly higher exposure to MEHP in Sarasota Bay dolphins. This finding is significant as this particular phthalate is common in polyvinyl chloride products, food packaging, wire covering, toys, and medical tubing.

The health consequences from phthalate exposure are currently unknown for bottlenose dolphins; however, rodent and human studies have demonstrated endocrine disrupting impacts leading to reduced fertility, abnormal reproductive organ development, increased breast cancer risk, and impacts on pregnancy outcomes.

Using long-term health data collected during Sarasota Bay dolphin health assessments, we have begun studies to explore indicators of endocrine disruption in phthalate-exposed dolphins.

While preliminary, we have evidence linking MEHP detection with increased free thyroxine (FT4) (thyroid hormones) in both female and male adult dolphins. Impacts to thyroid hormone levels can cause significant adverse health impacts, especially for developing fetuses, warranting further investigations of phthalate-mediated effects in dolphins.

Although the source of phthalate exposure in Sarasota Bay dolphins is currently unknown, we have evidence to suggest a plastic origin. Thanks to funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (a branch of the National Institutes of Health), over the next three years, our team will explore the potential for microplastic and chemical plasticizer exposure via consumption of contaminated fish. This research will rely on examinations of microplastic and phthalate exposure in bottlenose dolphins and their preferred prey. As apex predators with a long lifespan, year-round resident bottlenose dolphins can serve as gauges to detect disturbances in their local environment. As such, bottlenose dolphins can serve as excellent sentinels of environmental contaminant exposure for human communities — particularly coastal communities that rely on seafood as a primary food source.

— Leslie Hart, College of Charleston, and Miranda Dziobak, University of South Carolina